Keeping Your Dog Safe and Calm This Christmas and New Year’s

Every year we have to deal with these horrible things that cause misery to our animals and people like myself who are either neurodiverse or have a form of PTSD in which sound sensitivities can be a trigger.

It would be fantastic if we could get our countries to either ban them or only allow silent fireworks, but like anything animal welfare related or adaptations for the minority groups is an uphill battle.

The Firework campaign have been petitioning the government since 2013, if you would like to sign one of the three petitions that they recommend, you can do so here: https://fireworkcampaign.com/petitions-2/

With fireworks approaching, and as the weather is turning, facing the challenge of soothing their dogs during these noisy events can feel both challenging and overwhelming.

It can sometimes feel as though fireworks are only a once a year challenge, but when we look at New Year and other holidays and events people let off fireworks, it is a much larger scale of the challenges that we face with fireworks and of course thunder can also be another sound sensitivity that dogs struggle with.

Sound sensitivities affect around 40 – 50% of dogs in the UK and this percentage was only taken from a survey, where sampling does not include every canine home in the UK. According to the Vet record for Australia, 72% of companion animals are affected by fireworks which include dogs, cats, birds and horses. Reimer, (2019) Mann, et al (2024)

With around only 22.5% of survey respondents having sought professional help for their companion animal.

Let’s see how we can prepare for these stressful situations and create a calmer environment for your dog.

If you are aware that your dog has been traumatised by fireworks or storms in the past, first and foremost I would recommend speaking to your vet about possible medications around these events as a temporary measure, especially as we are running out of time before November 5th.

Gradual preparation and practice help set both you and your dog up for success. Incorporating comforting routines and enrichment activities before fireworks or thunderstorms arrive can help your dog feel secure, preventing stress signals tied to specific events. Desensitising your dog to loud sounds year-round can also make these events more manageable.

Close Curtains and Play Noise-Masking Sounds: Blocking outdoor stimuli by closing curtains and adding soothing sounds—whether calming music, white noise, or even the hum of household appliances—helps mask loud noises. White noise machines are often effective, and some offer options like brown, pink, and blue noise, which you can tailor to your dog’s preference.

You can also add temporary black out blinds that are used for babies to block out the sun, they cover all of the corners of the window, so this would be a very helpful addition in blocking out the flares and the light from the sky.

Offer Enrichment Activities and Chews:Provide distraction with mentally stimulating games, chews, and frozen treats like LickiMats and Kongs. Snuffle mats and destruction boxes can also help alleviate stress, giving your dog an outlet for their anxiety.

Provide Safe Spaces and Choices: Ensure your dog has cosy, safe spaces, and escape routes throughout the house. Respect their choice if they find comfort in a particular spot, even if it’s not the space you might expect. Creating small dens, like moving the couch from the wall or transforming a table into a shelter, can offer them a secure hideaway.

Use Comfort and Cuddling as Needed:

Comforting your dog is completely acceptable—cuddling won’t reinforce fear. If they come to you for reassurance, be there for them. Sitting close by and reading a book can also be grounding for them if they decide to hide.

Invest in a Subwoofer for Realistic Sound Desensitization:

Desensitisation sessions, where sounds are played at a low volume throughout the year, can be beneficial. A subwoofer, which simulates low bass frequencies and vibrations, can add realism to these sessions, making them more effective. Subwoofers are available on sites like Amazon or eBay for around £20. The second brilliant thing about subwoofers is you can move it, hide it and if you have the dog out of the room when setting up they won’t be able to easily identify it.

Prepare and Post a “Do Not Disturb” Notice: To avoid disruptions, consider posting a sign on the door and sharing on social media that you won’t be answering the door during the event to keep your dog calm.

Sound sensitivity affects a significant number of dogs, with approximately 40-50% showing anxiety around loud noises. Advanced preparation, such as playing recorded firework and thunder sounds gradually over time, can help desensitise dogs to the real thing, reducing their stress.

For thunderstorms, many dogs are sensitive to changes in barometric pressure, which can make desensitisation challenging. Extra measures, like keeping curtains closed and playing white noise, can make a big difference. White noise machines with adjustable frequency settings (e.g., pink noise for lower, more calming frequencies) can be helpful, especially if tailored to your dog’s comfort.

Evidence suggests that fluctuations in barometric pressure, which often occur before thunderstorms, can indeed impact dogs’ behavior and increase anxiety. Studies indicate that many dogs, like other animals, are sensitive to changes in atmospheric pressure, which they may associate with imminent adverse weather conditions such as thunderstorms.

Dogs possess heightened sensory capabilities, including the ability to detect subtle shifts in environmental factors, like pressure and humidity. Some research and observations suggest that a dog’s sensitive inner ear allows them to perceive these changes even before humans notice them, which can trigger anxiety if the dog has previously experienced a stressful event associated with similar conditions (e.g., thunderstorms or fireworks).

Clinical observations and case studies have found dogs to display anxious behaviours, such as pacing, panting, and hiding, often intensifying in dogs before and during storms. While some research focuses on the noise aspect, others point to additional sensory cues, like pressure drops, as potential triggers.

A study published in the Journal of Veterinary Behavior (2014) analysed patterns of storm-related anxiety and found that some dogs showed anxiety signs before storms even when there was no thunder or lightning. This suggests they could be reacting to atmospheric cues like barometric pressure or static electricity rather than sound alone. Reimer, (2020)

As storms approach, changes in barometric pressure are often accompanied by a rise in static electricity. Dogs’ fur can accumulate static charges, leading to discomfort and increased anxiety. This effect, coupled with pressure changes, can create a multi-sensory experience that might amplify stress in storm-phobic dogs.

Studies on livestock, wildlife, and companion animals suggest that many animals are responsive to barometric changes, as such fluctuations often signal environmental shifts, like rain or storms. Researchers have noted similar behavioural changes in birds and mammals, which, like dogs, show restlessness, shelter-seeking, and altered eating or sleeping patterns during these times.

These findings help explain why some dogs appear nervous or agitated even before a storm becomes visible or audible. Knowing this, dog guardians can prepare in advance by creating a safe, comforting environment if they notice their dog’s behavior shifting due to pressure changes.

While research on barometric pressure specifically in dogs is somewhat limited, existing studies and extensive anecdotal evidence from veterinarians and behaviourists support the theory that pressure changes can trigger or worsen anxiety in many dogs. Okamoto, et al., (2024)

Fear is a state which is induced by low intensity stimuli which is very specific, this creates a phobia. Blackwell, (2013)

Statistical data has also shown that 90% of dogs with a thunder phobia also have a noise phobia and 75% of dogs with a noise phobia also present with a thunder phobia. Overall, K. et al., (2001)

We know from emotionally challenged dogs that cortisol levels spike during times of distress for dogs, with a thunder phobia it has been found that the cortisol not only spikes but doubles in this spike. This acute stress can cause neuroscientific changes. Koolhaas, (1997)

Chronic stress is also likely to develop due to the development of fearful memories following acute stress, as we know from sensory sensitivities chronic stress can cause unwellness, such as disease, cardiovascular disorders, obesity, immunity abnormalities,changes in endocrine system insulin resistance and nervous system impairments. McEwen, (2005)

Thunder and firework phobias are not just limited to the UK, US and Australia, Finland have also documented 32% of dogs with thunder and fireworks phobias. Salonen, et al (2020) and 40 – 60% of dogs affected in Japan. Kurachi, et al (2017)

The other factors that have been found to affect dogs and their noise sensitivities and thunder phobias has also been linked to pain and unwellness through disease processes. Camps, (2019), Fagundes., (2018) Mills, et al (2020)

Given the strong bond between humans and dogs, along with dogs’ capacity for cross-species emotional recognition and empathy (Albuquerque. N., et al, (2016); Custance, & Mayer, (2012), it’s possible that owner characteristics could influence canine behavior. Various studies have examined links between dog behavior problems and their owners’ personality traits Dodman, (2018); Gobbo. & Zupan, (2020); Konok, (2015), though the specific link between dog and owner fear of thunder is unclear Blackwell et al. (2013).

I would like to stress here the importance of the results and research being unclear if dog guardians are an influence on their dog’s fear. I really dislike this language and felt it needs to be addressed here, should you look up the paper.

Additionally, limited evidence examines the influence of the living environment on dog behavior (Hetts et al., 1992; Hubrecht et al., 1992; Kobelt et al., (2003). Sound-blocking capacities in different living spaces could impact dogs’ sensitivity to external noise (Hiramatsu & Tabata., (2017), with environmental noise fear and sensitivity often interrelated (Handegård, et al., 2020; Riemer, (2019). Which indicates that residence type may play a role in thunder fear.

Factors like sensitization from repeated exposure, chronic stress following habituation, trauma-based learning, and social learning also contribute to phobias Mills, (2005). More frequent thunderstorm exposure and experiences during socialisation could increase thunder fear risk Blackwell, (2013); Riemer, (2019); Walker, (1997).

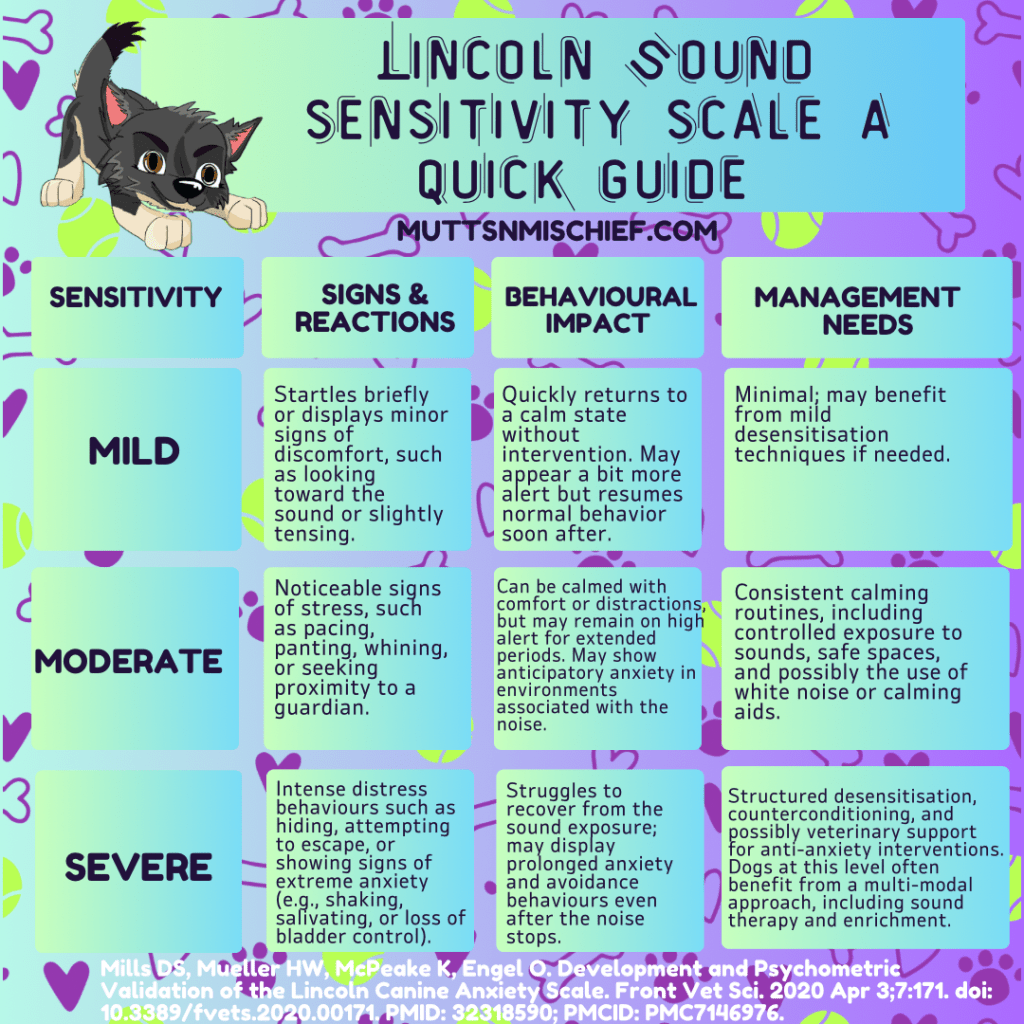

Whether you have a puppy, adolescent, adult or senior dog, you can use a tool called the Sound Sensitivity Scale which is a tool for dog guardians that helps identify and measure the degree of a dog’s sensitivity to noises like thunderstorms, fireworks, and other loud or sudden sounds. Developed to aid in assessing sound-related anxieties, this scale ranges from mild to severe sensitivity levels.

Using this scale helps identify the degree of a dog’s sound sensitivity, allowing guardians and behaviourists to create tailored management plans that align with the dog’s specific needs. This assessment is also helpful in tracking a dog’s progress if they are undergoing sound desensitisation or anxiety-reduction training.

Regular readers will be familiar with myself giving out tools and resources which are normally obscure to find and or difficult to understand. If you can use this tool and keep a journal this will also help you in showing the distress your dog is in. Here’s an outline of the scale:

Mild Sensitivity

Reactions: Startles briefly or displays minor signs of discomfort, such as looking toward the sound or slightly tensing.

Behavioural Impact: Quickly returns to a calm state without intervention. May appear a bit more alert but resumes normal behavior soon after.

Management Needs: Minimal; may benefit from mild desensitisation techniques if needed.

Moderate Sensitivity

Reactions: Noticeable signs of stress, such as pacing, panting, whining, or seeking proximity to a guardian.

Behavioural Impact: Can be calmed with comfort or distractions, but may remain on high alert for extended periods. May show anticipatory anxiety in environments associated with the noise.

Management Needs: Consistent calming routines, including controlled exposure to sounds, safe spaces, and possibly the use of white noise or calming aids.

Severe Sensitivity

Reactions: Intense distress behaviours such as hiding, attempting to escape, or showing signs of extreme anxiety (e.g., shaking, salivating, or loss of bladder control).

Behavioural Impact: Struggles to recover from the sound exposure; may display prolonged anxiety and avoidance behaviours even after the noise stops.

Management Needs: Structured desensitisation, counterconditioning, and possibly veterinary support for anti-anxiety interventions. Dogs at this level often benefit from a multi-modal approach, including sound therapy and enrichment.

To conclude, managing sound sensitivities in dogs, especially those triggered by fireworks and thunderstorms, requires a thoughtful, multi-faceted approach. From environmental adjustments to desensitisation techniques, dog guardians can play a crucial role in helping their dogs navigate these distressing events. Preparing by incorporating comforting routines, using sound-masking devices, creating safe spaces, and providing enrichment can all aid in creating a calmer atmosphere. Additionally, the Sound Sensitivity Scale can help assess your dog’s level of sensitivity, allowing you to track progress and tailor support according to their needs.

Sound sensitivities are common, affecting a large percentage of dogs, yet only a fraction of guardians seek professional assistance. As fireworks season approaches, taking steps to prepare and consider medical support if needed can make a significant difference for dogs and their guardians alike. By staying informed and equipped with tools like the Sound Sensitivity Scale, we can help reduce stress for dogs facing sound-induced anxiety and build environments that prioritise their emotional well-being.

Resources

Fireworks desensitisation https://youtu.be/DygQqzykxFk?si=_zq8AzYns1Ytn_o3

Thunder and lightning desensitisation https://youtu.be/_nqpdl7a7CY?si=KFh2_dCYh05giFRw

Enrichment preparation https://youtu.be/KLTdr6c6vqI

I have also included a graphic as a quick tool to refer to, to measure your dog’s sound sensitivities from the Sound Sensitivity Scale.

By proactively creating a soothing environment and gradually desensitising your dog, you’ll help them build resilience so that noise, firework and thunder phobias do not have to be a forever behaviour and you can improve your dog’s welfare!

References

- Riemer, S. (2019). Not a one-way road—Severity, progression and prevention of firework fears in dogs. PLOS ONE, 14(9), p.e0218150. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0218150.

- Mann, A., Hall, E., McGowan, C. and Quain, A. (2024). A survey investigating owner perceptions and management of fireworks‐associated fear in dogs in the Greater Sydney area. Australian Veterinary Journal, 102(10), pp.491–502. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/avj.13357.

- Riemer, S. (2020). Effectiveness of treatments for firework fears in dogs. Journal of Veterinary Behavior, 37. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jveb.2020.04.005.

- Okamoto, K., Inoue, K., Kawai, J., Yamauchi, H., Hisamoto, S., Nishisue, K., Koyama, S., Satoh, T., Tsushima, M. and Irimajiri, M. (2024). Factors influencing the development of canine fear of thunder. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, [online] 270, p.106139. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2023.106139.

- E.J. Blackwell, J.W.S. Bradshaw, R.A. Casey (2013). Fear responses to noises in domestic dogs: Prevalence, risk factors and co-occurrence with other fear related behaviour. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci., 145 (1–2) pp. 15-25, 10.1016/j.applanim.2012.12.004

- K.L. Overall, A.E. Dunham, D. FrankFrequency of nonspecific clinical signs in dogs with separation anxiety, thunderstorm phobia, and noise phobia, alone or in combinationJ. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc., 219 (4) (2001), pp. 467-473, 10.2460/javma.2001.219.467

- J.M. Koolhaas, P. Meerlo, S.F. de Boer, J.H. Strubbe, B.Bohus. (1997) The temporal dynamics of the stress responseNeurosci. Biobehav. Rev., 21 (6) (1997), pp. 775-782, 10.1016/S0149-7634(96)00057-7

- B.S. Mcewen. (2005) Stressed or stressed out: What is the difference?J. Psychiatry Neurosci., 30 (5)

- M. Salonen, S. Sulkama, S. Mikkola, J. Puurunen, E.Hakanen, K. Tiira, C. Araujo, H. Lohi. (2020). Prevalence, comorbidity, and breed differences in canine anxiety in 13,700 Finnish pet dogs. Sci. Rep., 10 (1) 10.1038/s41598-020-59837-z

- T. Kurachi, M. Irimajiri, Y. Mizuta, T. Satoh. (2017) Dogs predisposed to anxiety disorders and related factors in Japan. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci., 196, pp. 69-75, 10.1016/j.applanim.2017.06.018

- T. Camps, M. Amat, X. Manteca (2019). A review of medical conditions and behavioural problems in dogs and cats. Animals, 9 (12), 10.3390/ani9121133

- A.L.L. Fagundes, L. Hewison, K.J. McPeake, H. Zulch, D.S. Mills. (2018). Noise sensitivities in dogs: An exploration of signs in dogs with and without musculoskeletal pain using qualitative content analysis. Front. Vet. Sci., 5 (17), 10.3389/fvets.2018.00017

- D.S. Mills, I. Demontigny-Bédard, M. Gruen, M.P.Klinck, K.J. McPeake, A.M. Barcelos, L. Hewison, H.Van Haevermaet, S. Denenberg, H. Hauser, C. Koch, K.Ballantyne, C. Wilson, C.V. Mathkari, J. Pounder, E.Garcia, P. Darder, J. Fatjó, E. Levine. (2020). Pain and problem behavior in cats and dogs. Animals, 10 (2), 10.3390/ani10020318

- N. Albuquerque, K. Guo, A. Wilkinson, C. Savalli, E.Otta, D. Mills. (2016). Dogs recognize dog and human emotionsBiol. Lett., 12 (1), 10.1098/rsbl.2015.0883

- D. Custance, J. Mayer (2012). Empathic-like responding by domestic dogs (Canis familiaris) to distress in humans: An exploratory studyAnim. Cogn., 15 (5), pp. 851-859, 10.1007/s10071-012-0510-1

- N.H. Dodman, D.C. Brown, J.A. Serpel (2018). Associations between owner personality and psychological status and the prevalence of canine behavior problems. PLoS ONE, 13 (2), 10.1371/journal.pone.0192846

- E. Gobbo, M. Zupan. (2020) Dogs’ sociability, owners’ neuroticism and attachment style to pets as predictors of dog aggression. Animals, 10 (2), 10.3390/ani10020315

- V. Konok, A. Kosztolányi, W. Rainer, B. Mutschler, U.Halsband, Á. Miklósi. Influence of owners’ attachment style and personality on their dogs’ (Canis familiaris) separation-related disorder. (2015). PLoS ONE, 10 (2), 10.1371/journal.pone.0118375

- S. Hetts, J. Derrell Clark, J.P. Calpin, C.E. Arnold, J.M.Mateo. (1992). Influence of housing conditions on beagle behaviour. Appl. Anim. Behav., 34, pp. 137-155.

- R.C. Hubrecht, J.A. Serpell, T.B. Poole. (1992). Correlates of pen size and housing conditions on the behaviour of kennelled dogsAppl. Anim. Behav. Sci., 34 (4), pp. 365-383, 10.1016/S0168-1591(05)80096-6

- A.J. Kobelt, P.H. Hemsworth, J.L. Barnett, G.J. Coleman. A survey of dog ownership in suburban Australia—Conditions and behaviour problems. (2003). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci., 82 (2), pp. 137-148, 10.1016/S0168-1591(03)00062-5

- T. Hiramatsu, A. Tabata. (2017) Sound Insulation Performance and Sound Insulation Design Principles for Multi-Unit Residences. Acoust. Sci. Technol., 73 (2), pp. 123-130, 10.20697/jasj.73.2_123

- K.W. Handegård, L.M. Storengen, F. Lingaas. (2020). Noise reactivity in standard poodles and Irish soft-coated wheaten terriers. J. Vet. Behav., 36, pp. 4-12, 10.1016/j.jveb.2020.01.002

- Riemer.S. (2019). Not a one-way road—Severity, progression and prevention of firework fears in dogs. PLoS ONE, 14 (9), 10.1371/journal.pone.0218150

- R. Walker, J. Fisher, P. Neville. (1997). The treatment of phobias in the dog. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci., 52, pp. 275-289

Leave a comment